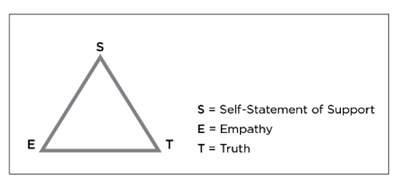

If you’re reading this article, chances are you might be familiar with BPD and involved in the life of someone who has this diagnosis. It’s important to know that while BPD is the label used to define the diagnostic criteria, there is an individual underneath who is experiencing pain and suffering. This post is designed to help you support the person underneath the diagnosis, while also honoring your own needs in the relationship. Many of these strategies are adopted from a highly-rated book called “Talking to a Loved One with Borderline Personality Disorder” by Dr. Jerold Kreisman. You can find the book here. The SET framework is an acronym founded by Dr. Kreisman designed to help people who have a loved one with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD). It’s an acronym that uses the format S(upport) E(mpathy) T(ruth). The SET framework was designed to help with the following:

- Create a setting that helps the person recognize unproductive behaviour and alter it;

- Focus on improving mood and control of destructive behaviours;

- Work through conflict, destructive behaviour, or any other dialogue that has created strain in the relationship.

Let’s start by breaking down the framework!

Support

This part of the framework emphasizes the need for you to express a personal statement of concern and commitment to the person with BPD. One of the ongoing difficulties for people with BPD is fear of abandonment or rejection. This means that the person may be hypersensitive to comments around the relationship ending, the implementation of boundaries, or conditions around your support. Beginning the conversation through an expression of support, it lays the groundwork for the conversation to be one that’s focused on your commitment to the relationship. To express support, it’s easiest to use “I” statements about your pledge to be there for your loved one. Some examples might include “I am really concerned about how you are feeling” “I’m worried about the impact this is having on you” “I want to try and help”.

Empathy

This part of the framework emphasizes how the other person is feeling. Empathy is a critical component of any relationship, but particularly important in relationships with someone who has BPD given the emotional dysregulation that these individuals often feel. Integrating empathy means focusing on the person’s experience and emotions, ultimately trying to view the situations through their unique perspective and lens. Empathy doesn’t mean you need to feel the same way as them, but instead it’s about stepping into their shoes to try and engaging in perspective taking about how they are impacted. Some examples of empathetic statements might be “It sounds like you’re feeling so much pain right now” “This must be incredibly hard to go through” “It must be exhausting having to endure this scenario right now”.

It’s important to differentiate between empathy and sympathy. The primary difference is that empathy is feeling with someone and sympathy is feeling for someone. Empathy is “this must be so hard to go through” and sympathy is “I feel so bad for you right now”. Brene Brown is an author and expert on empathy. You can check out her video on the difference between empathy and sympathy here.

Truth

The integration of truth is an incredibly important part of the framework because this allows you to integrate your perspective on the issues at hand. It places the responsibility back on the person with BPD to address their participation in destructive behaviour. Support and empathy are still acknowledged, but an emphasis is placed to address the facts of the situation in a neutral, matter of fact way. This part is likely going to be the most difficult for both parties as it involves shedding light on topics that could be difficult to address. However, this is not designed to be a confrontation, “hard truth”, or “tough love” statement, instead it addresses the issue at hand but focuses on practical options of what can be done to deal with it. Truth statements should never involve blame, shame or should statements like “Look at this mess you got us into” or “This wouldn’t have happened if you would have just done what I said to begin with”. One final part about truth statements is that they should be kept in the present and not the past. Statements that focus on the past are likely to derail the conversation and make it harder to keep following the SET framework.

The SET framework might lead to further dialogue about the issue at hand. For example, Sarah might start feel upset and state that she doesn’t want to do anything to address her self-harm behaviour. Or she might claim that Susan doesn’t understand how she feels. If that happens, that’s ok! It’s a signal to revisit and reinforce the SET framework again.

“Sarah, I understand that you’re feeling like I don’t get what you’re going through. I want you to know that I love you, I am here for you, and I am committed to working through this together.” (support)

“I hear your concerns that you feel no one can understand what this must be like. ” (empathy)

“I want to help you in whatever way I can, but a priority is your physical safety. Your self-harm is placing your safety at risk and jeopardizing your wellbeing. How can we work together to support you through these painful emotions instead of self-harm?” (truth)

One of the challenging parts of the SET framework is understanding and maintaining your own emotions. If you feel that unfair accusations are being made or there are threats of destructive behaviour, it makes sense to feel your own emotional response. It’s very important for you to keep focused on the objectives and outcomes you have in this interaction.

Let’s look at another scenario. In this example James and Dawn are helping to support their adult son, Duncan, who recently moved back home after he was laid off work. James and Dawn are feeling frustrated about Duncan being messy in the home, not contributing to chores, and ignoring their requests to help out.

“Duncan, as your parents we want to do what we can to help you during this difficult time. We care so much about you and are here to lend a hand when we can” (support).

“We understand this has been really hard for you. You always spoke about how much you loved your job and it must have been so painful to hear the news that you were laid off” (empathy).

“One thing we do expect while you are living here is to be responsible and help out around the house. This is the “rent” that we are asking for from you. Things like cutting the grass, unloading the dishwasher, and helping out with chores are the expectations we have about your contributions to the household. If you are not able to help out with the “rent” at the house, then we cannot have you stay here” (truth).

Other strategies for supporting someone with BPD:

- Anticipate. Rehearse how you might support someone with BPD by running through the conversation in your mind ahead of time. Think of how you might phrase your communication to help you better regulate your emotions.

- Emphasize the positive. It is helpful in any relationship to focus and acknowledges strengths and achievements. We are far more likely to respond well to positive reinforcement than negative reinforcement. Statements like “I’m really proud of how you responded in that situation” can be important for maintaining the support in the relationship.

- Ask questions. When facing destructive behaviours or conflict in the relationship, it’s a great idea to ask for input from the other person. Questions like “How do you think we should manage this?” and “What do you think the next step should be?” make it a collaborative process.